De/Reconstruction - How Positive Fragmentation Challenges High Art

Review of Positive Fragmentation at Bellevue Art Museum

Written by TeenTix Newsroom Writer Sylvia Jarman and edited by Teen Editorial Staff Member Aamina Mughal

The concept of “positive fragmentation” existed long before the exhibition at the Bellevue Art Museum. The term was coined by the feminist art critic Lucy Lippard, in her 1978 essay, Making Something from Nothing. Lippard’s essay dissects the disparity in male and female representation in high art. Lippard notes that art produced by women tends to be labeled as hobbyist and nothing more by those discussing high art. She goes on to state that the same can be said for certain art mediums, specifically printmaking, as it is seen as replicable and, thus, less rare or valuable. With Lippard’s idea here in mind, there is a clear intersection for female artists whose primary medium is printmaking, who have gone almost entirely overlooked because of this. Enter “positive fragmentation,” a term Lippard uses to describe the aesthetic of these artists and what their work accomplishes. “Positive fragmentation” is described as eclectic, bombastic, the “collage aesthetic,” and Lippard posits that it lends itself incredibly well to marginalized artists because of its inherent willingness to deconstruct and then reconstruct the notions of high and low art. The exhibit Positive Fragmentation, bearing the same name as Lippard’s theory, aims to the ideas she had outlined, showcasing over 200 prints by 21 contemporary women printmakers that demonstrate the sheer power of the medium, totally averting the preconceived notion that prints are incapable of being expressive and unique.

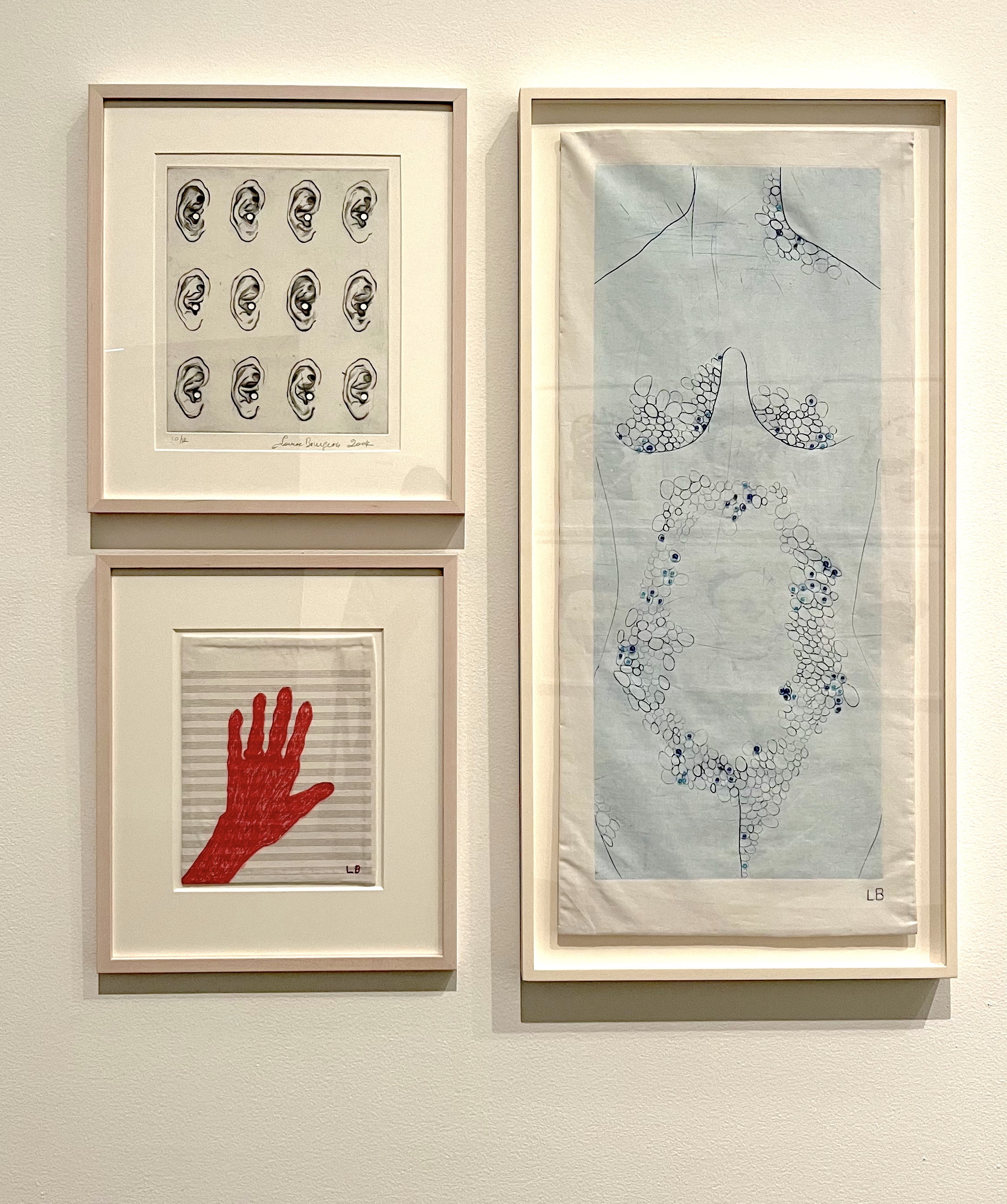

The exhibition is found on the third floor of the Bellevue Art Museum (BAM), a sprawling space lined wall-to-wall with prints from remarkable artists such as Betye Saar, Wendy Red Star, Louise Bourgeois, and many more. Exhibiting so many pieces in a relatively small space is a difficult task. For many other gallery spaces, the exhibition would have felt confusing and hectic, yet the BAM handles it incredibly well. There is a good flow to the gallery, with the pieces displayed in groups of several smaller subcategories: time, bodies, art history, meaning, subtext, and critique. With this method of display, the viewer feels a sense of cohesion, and it makes the task of displaying such a sheer number of pieces much less daunting. BAM is a smaller space, but this is by no means a negative quality. To an exhibition such as Positive Fragmentation, such a small and intimate setting lends itself well. It makes the exhibition feel all the more personal like the viewer has a greater opportunity to connect with the art, and it neatly avoids the hollow or empty feeling that certain larger spaces often have.

As Lippard states in her essay, both women and printmaking have historically underrepresented, and women in printmaking have been doubly shunned to the shadowy background of art history. This is exactly why I was so enthused to see an exhibit that entirely focused on this specific group of artists. Virtually every method of printmaking has been vastly ignored in discussions of high art outside of a few artists. They are deemed “less than” due to the replicable nature of the medium. However, Positive Fragmentation serves to prove that printmaking is just as if not more meaningful and unique as any painting or sculpture. My favorite artist in the exhibition, Louise Bourgeois, has a collection of prints featured that centers on the human body and societal expectations regarding it. Bourgeois’s work is masterful and deep, making incredible use of symbolism and composition to succinctly express the emotions behind her work. The fact that the works are prints does nothing to detract from the incredible meaning of it, affirming the theories behind Positive Fragmentation.

Bourgeois appealed to my sensibilities, but she is far from the only artist featured with deeply profound and meaningful art on display. Mickalene Thomas’s compositions effortlessly blend elements of both craft and high art, using collage elements with materials like gold leaf. Julie Mehretu combines contemporary street art with ancient texts and mythology, creating an intriguing juxtaposition. Christiane Baumgartner has the towering Stairway to Heaven series, an amazingly intricate rendition of a waterfall from several different angles and dates observing the passage of time. Every piece in Positive Fragmentation has prints and photographs elevated to new heights because of the sheer versatility of the medium, seen in the great differences between each artist.

My sole issue with the exhibition lies within the curation. The gallery aims to categorize the prints by subject matter, which does sort of help the viewer get their bearings as they enter, but it does raise some concerns. I felt as though it complicated the meaning of the exhibition. By categorizing each piece, it felt like there was an attempt at making several connections that just weren’t there. In doing this, the exhibit feels like it lacks faith in its basis as if the concept of positive fragmentation wasn't enough to stand on its own. This opens up another concern that I had with the concept of categorization; it felt antithetical to the spirit of positive fragmentation as a concept. As Lippard had stated in her initial definition, positive fragmentation is meant to be chaotic, and by organizing the pieces featured into these neat little boxes, it feels like the exhibition is failing to recognize that, like they were trying to justify something that did not need to be justified. In doing so, it seems as though the standards that Positive Fragmentation meant to confront have now been upheld. It shows a level of doubt on the curator’s behalf as if the viewer would be unable to understand the idea of positive fragmentation because of how eclectic it is. It’s treated as a flaw, something to work around, just as it has been historically. The exhibition could have been much more profound had the vast differences between the featured pieces been embraced rather than poorly explained. The art of Positive Fragmentation is vibrant, bold, and unapologetic, and I can’t help but feel as though it’s been stifled by the way it is presented.

Though I was already quite fond of printmaking as a medium before attending the exhibition, I feel as though I left the Bellevue Art Museum with a much more nuanced view of the medium. It provided an opportunity to learn about many artists that I had never heard of before and all the ways that they modify and innovate printmaking, dissecting and breaking down the medium only to rebuild in a way that is much more vast and expressive, totally subverting the widely understood picture of printmaking. If I, someone who was already greatly in favor of printmaking, was able to gain so much from the exhibit, I can only imagine how much it would impact one who is skeptical about it. Lippard’s theory may seem difficult to visualize initially; to one unfamiliar with art discourse, positive fragmentation might seem nonsensical or confusing. Why glorify disorganization? But the exhibition, with its incredible collection of varied, symbolic, innovative, and simply gorgeous prints is an incredible representation of Lippard’s theory, proving the importance of women in printmaking in art history and the beauty of positive fragmentation.

Lead Photo Credit: Detail of DeLuxe by Ellen Gallagher, photo courtesy of Coco Allred

The TeenTix Newsroom is a group of teen writers led by the Teen Editorial Staff. For each review, Newsroom writers work individually with a teen editor to polish their writing for publication. The Teen Editorial Staff is made up of 5 teens who curate the review portion of the TeenTix blog. More information about the Teen Editorial Staff can be found HERE.

The TeenTix Press Corps promotes critical thinking, communication, and information literacy through criticism and journalism practice for teens. For more information about the Press Corps program see HERE.