The Devil Strikes at Noir City Festival

Review of The Devil Strikes at Night at SIFF

Written by TeenTix Newsroom Writer Amy Harris and edited by Teen Editor Tova Gaster

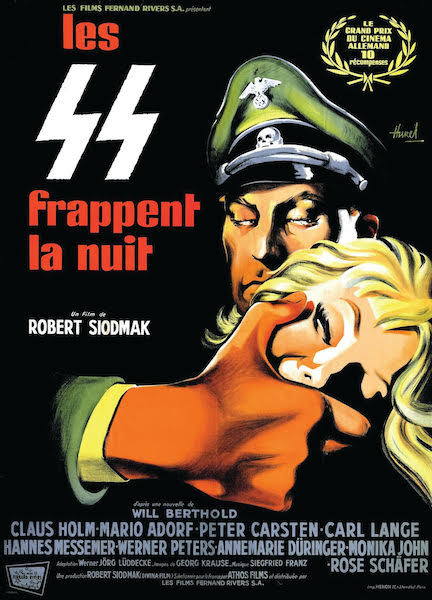

Thursday, February 20 marked the culmination of the traveling Noir City Festival in Seattle. Hosted by the “Czar of Noir,” Eddie Muller, the penultimate film was the 1957 German feature, The Devil Strikes at Night.

When doors opened at 5:15 p.m., benefactors flocked to the donor reception, awash with wine, while others saved seats in the theater. Onstage, the Dmitri Matheny trio opened, floating through a half-hour of both the exotic and familiar. While technically adept, the music pertained less to the film or noir mood and more to the superficial Egyptian-themed trimmings of the venue.

Audience now settled, Muller took the stage to introduce the film.

“This is a pertinent film,” he began. “Americans don’t get to see films about Nazi Germany—that is, everyday people in Nazi Germany. The ones who didn’t get out.”

Directed by “the greatest director of film noir, ever,” according to Muller, this Robert Siodmak picture was his first after his return to Germany after he had fled to Hollywood during World War II. It aimed to help Siodmak explore the homeland he was forced to abandon.

“It’s a social commentary on the ideologies that held sway in that era. And, if you recognize things—yes, I do too,” Muller added, with a morbid wink.

The film follows Berlin homicide detective Axel Kersten’s (Claus Holm) quest to exonerate a womanizing, but wrongfully accused petty officer in the Nazi party (Werner Peters) in 1944. With the help of a perky police secretary (Annemarie Düringer,) he tracks down the real culprit, a mentally-ill serial killer (Mario Adorf) hiding in plain sight. The Gestapo encourages the investigation with the intent of demonstrating the inferiority of foreign-born people. But, when the true killer is a full-blooded German handyman, they cover up the affair, frame the wrong man, and doom Kersten to the Eastern front for his insubordination. The theme of governmental meddling to advance internal propaganda and as opposed to protecting its citizens is what Muller referenced during his introduction, in a modern era at the zenith of spin-doctoring.

“I merely did my duty, that’s all,” protested Kersten, in an ironic echo of the oft-used Nuremberg trial line. Siodmak not only explicitly brings attention to the hypocrisy prolific throughout the Third Reich, but creates evocative imagery through the juxtaposition of the joyous or mundane with Nazi iconography to deeply unsettling effect. An exercise in pleasure, vice, and corruption, the film is unapologetically brash. Holm’s unconventionally soft-spoken leading man derives motivation from a sense of strong moral conviction instead of machismo or superiority, setting his personality apart from the government he’s surrounded by and his performance apart from other comparable protagonists. A chainsmoking girl-Friday, a cynical waitress, a libertine officer with delusions of grandeur, and an ever-present Gestapo captain make up the rest of the main cast.

While this film may relish in the conventions of noir, such as the sordid crime story, low angles, and chiaroscuro lighting, the majority of the film is set during the day time. Grittiness is lent to the plot by way of the wartime setting. Constant talk of rationing, air raids, destruction on the fronts, and the destitution of smaller villages did well making sunny scenes feel oppressive. The Gestapo are portrayed with villainy that isn’t far from the truth, but occasionally felt campy because of some cartoonish qualities (a henchman with a blind eye? Come on.) Hannes Messemer delivered a brooding, but hypocritically human Gestapo superior, whose interests lie solely among the parties he throws in his lavish chateau and the perception of the Nazi party.

The depiction of justice comes across as slightly exaggerated, the piecemeal nature of the score more inconsistent than emotive, and editing is slow-paced with lengthy and repetitive sequences of running or driving. The portrayal of mental illness is more slapstick and insensitive than accurate, but expected from an era in which most patients would be confined in sanitariums instead of receiving legitimate treatment. Adorf did manage to bring some authenticity to the performance, his mannerisms adding realism to the otherwise hyperbolic role. While it lacks nuance and is less a cerebral exploration of corruption and more a straightforward depiction of injustice, this is a consequence of the time and style of the first half-century of cinema. It may not be as entertaining to modern audiences as it was to those in 1957, but it still retains its merits as the effort of a brilliant director struggling to reconcile his fragmented country and as an early exploration of criticism through film.

Overlooking the preferences of a more contemporary viewership, The Devil Strikes at Night is solidly implanted within the film noir ethos. A return to form by the genre-defining Siodmak, it is a broadening watch for fans of noir, but in all honesty, too dull for most.

The Noir City Festival ran at SIFF February 14 - 20, 2020. For event information see here.

Lead photo caption: Rose Schafer and Mario Adorf in The Devil Strikes at Night.

The TeenTix Newsroom is a group of teen writers led by the Teen Editorial Staff. For each review, Newsroom writers work individually with a teen editor to polish their writing for publication. The Teen Editorial Staff is made up of 6 teens who curate the review portion of the TeenTix blog. More information about the Teen Editorial Staff can be found HERE.

The TeenTix Press Corps promotes critical thinking, communication, and information literacy through criticism and journalism practice for teens. For more information about the Press Corps program see HERE.